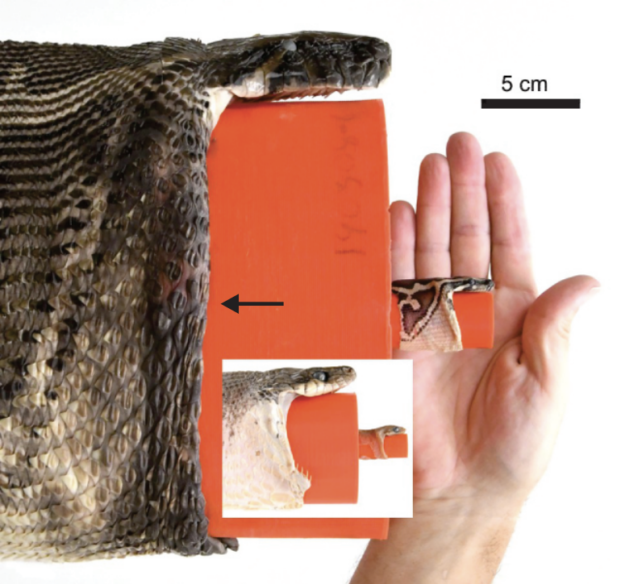

Burmese python are huge, growing up to 5 meters (16 feet) long. But their sheer size alone can’t explain their incredible gape – the amount the animal can open its mouth – required to ingest prey as large as deer or alligators.

A new study details how Burmese pythons (Python molorus bivittatus) have evolved a unique feature that allows their jaws to stretch wide enough to ingest prey up to six times larger than some similarly sized snakes can eat.

Despite their voracious appetite, wild Burmese pythons are actually vulnerable in their native Southeast Asia, due partly to habitat loss wrought by humans.

But in Florida, where they’ve been introduced, they are decimating native species and damaging the ecosystem by eating almost everything in sight.

“The Everglades ecosystem is changing in real-time based on one species, the Burmese python,” says Ian Bartoszek, an environmental scientist for the Conservancy of Southwest Florida.

In the new study, Bartoszek and three other researchers took a closer look at the biology of this massive snake, specifically its ability to eat virtually any creature it encounters.

Also Read: Chilean Scientists Discover 12,000-Year-Old Elephant Remains

To help their already-large mouths open even wider, the study found, Burmese pythons evolved a special feature: Super-stretchy skin between their lower jaws that allows them to gobble down animals even bigger than what their highly mobile jaws alone would permit

Because snakes tend to swallow their prey whole, without chewing it first, their gape is a key factor in determining what they can eat.

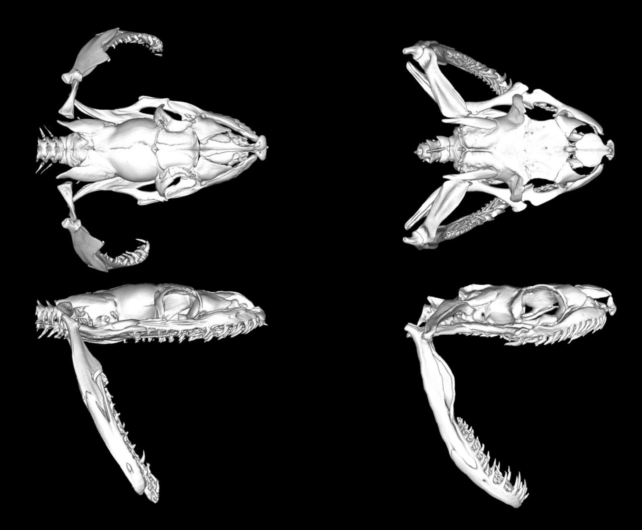

Unlike the lower jaws of humans and other mammals, the lower jawbones of snakes are not fused but only loosely connected with an elastic ligament, allowing their mouths to open wider.

Yet while expandable jaws may be standard for snakes, the super-stretchy skin of Burmese pythons’ lower jaws goes to a new level of elasticity, explains study co-author and University of Cincinnati evolutionary biologist Bruce Jayne.

“The stretchy skin between left and right lower jaws is radically different in pythons. Just over 40 percent of their total gape area on average is from stretchy skin,” Jayne says.

“Even after you correct for their large heads, their gape is enormous.”

To see how the gape of snakes compares to their body size, Jayne and his colleagues also examined the gape of wild-caught and captive brown tree snakes (Boiga irregularis) along with that of Burmese pythons.

These smaller snakes, which are mildly venomous, hunt birds and other small prey in forest canopies.

By measuring snakes as well as their potential prey, the researchers could estimate the largest animals the snakes could eat, along with the relative benefits of eating different prey options, ranging from rats and rabbits to alligators and white-tailed deer.

The data suggest that smaller snakes have more to gain from an enlarged gape size that enables them to eat relatively larger prey. That means baby pythons have a leg up (figuratively) on other snakes their size since they can exploit a wider range of prey.

Greater body size not only provides a broader menu for snakes, the researchers add, but it also helps them stay off the menu for other predators.

“Once those pythons get to a reasonable size, it’s pretty much just alligators that can eat them,” Jayne says. “And pythons eat alligators.”

Past research shows that constrictors such as Burmese pythons kill their prey not by suffocating it, but by cutting off the helpless animals’ blood flow.

While the new research is more about understanding a biological curiosity than figuring out how to control an invasive species, it could at least help scientists anticipate the cascading effects of Burmese pythons on wetland ecosystems.

“It’s not going to help to control them,” Jayne says. “But it can help us understand the impact of invasive species. If you know how big the snakes get and how long it takes for them to get that size, you can place a rough upper limit on what resources the snake could be expected to exploit.”

The study was published in Integrative Organismal Biology.